May is a great time to see new art in Iceland. In most places, graduation exhibitions are tucked away in art schools and universities. Not so in Iceland! On May 6, the MA Degree show by Design and Fine Art students of Iceland Academy of the Arts opened at Gerðarsafn – Kópavogur Art Museum. The freshness, range and innovativeness of the works on show was impressive. Standout works for Carol included a work devoted to the applications of Icelandic wool in a sustainable future, a drawing work entitled 7,182kg by Ásgrímur Þórhallson, a sculpture titled Weathered steel, clay by Mia Van Veen, and a quirky video performance work.

A week later, on 13 May, the Bachelor of Arts degree show opened at Hafnarhús (Reykjavík Art Gallery’s contemporary art venue). This much bigger exhibition spanned several floors of the gallery and included works by students of Fine Art, Visual Communication, Architecture, Fashion Design and Product Design. The sense of energy was palpable, as graduating students (often seen bearing small bouquets) mingled with viewers eager to see their work and chat with the artists. The presence of a number of interactive and performance works added to the buzz; in one room a live tattooing event was taking place; at one end of the huge atrium a painter worked expressionistically while at the other end a sombre faced, near naked woman crawled interminably on a slow treadmill.

The variety of approaches to installation of the art was also refreshing. The walls of the gallery where the Product Design works were on display for example were painted black, and the show was cast in darkness apart from the lights that illuminated various pieces. This had the effect of creating, within a limited space, distinct spaces that allowed the viewer to focus her attention on the separate pieces. A standout work here was Hrefna Sigurðardóttir’s piece devoted to Iceland’s marshes. It comprised a number of elements – a set of brushes reminiscent of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy brushes made from the angelica stems and the cottongrass that grows in the marshes, colour charts painted with varying tones and densities of marsh mud, and a wall mounted video that shows the artist bathing in the (freezing cold) mud of the marsh as if it were a beauty or health treatment. This work had a message: why can’t we appreciate the marshes for what they are? Viewers learn that the desire to make use of them is problematic. They were mostly drained so the land could be used for agriculture, but in fact that seldom eventuated. The consequence is that the drained land now accounts for 70% of Iceland’s carbon emissions.

Other Reykjavík gallery highlights

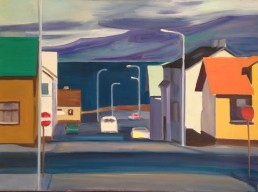

Of the other exhibitions Carol visited in Reykjavík, especially impressive were the retrospective of Icelandic artist, Louisa Matthíasdóttir, titled Calm, at Reykjavík Art Museum – Kjarvalsstaðir. Her bold brushwork and use of colour, and the confidence of her self-portraits, are a delight.

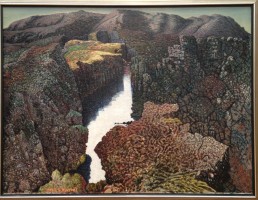

Also, the depiction of the Icelandic landscape found in the works of Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval, in whose honour the museum is named, was inspiring. A wall text noted that his works had a great influence on local perceptions of Iceland. Remarkable is the manner in which the dense network of brushstrokes captures the scarred surface of igneous rock and the complex hues of mosses while emphasising the weighty power and grandeur of this spectacular environment.

Two new exhibitions opened at Hafnarborg on 27 May

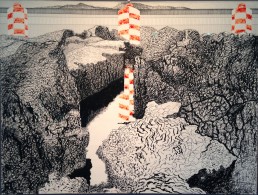

On the ground floor was an exhibition of poetic drawing-based work titled Without dreams all is dead (the title borrows a line from a poem by Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness) which consists of the work of two Icelandic artists – one who is resident in Montreal (Una Lorenzen), the other lives in California (Sara Gunnarsdóttir). Una Lorenzen’s part of the exhibition spans drawing and animation while Sara Gunnarsdóttir’s consists of framed embroidery works accompanied by a cabinet of journal drawings.

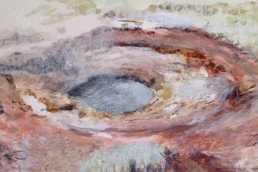

The new exhibition on the first floor of Hafnarborg, titled Land Seen: In the footsteps of Einer Falur Ingólfsson, also functions as a dialogue, this time between an Icelandic photographer and a long dead Danish illustrator. The photographer describes the relationship thus: “For three years, from 2014 to 2016, the Danish artist Johannes Larsen (1867-1961) was my guide while travelling around and photographing Iceland. Larsen was in Iceland during the summers of 1927 and 1930 and made over 300 drawings of sites mentioned in the Sagas of the Icelanders for a three-volume edition of the sagas to be published by the Danish Press Gyldendal between 1930 and 1932. Almost ninety years later, I followed in Larsen’s footsteps, working with a large sheet film camera in many of the same places he visited.”